Investigative tree-ring analysis on Musical Instruments

Peter

Ratcliff

DENDROCHRONOLOGY Ltd

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

VIOLIN

CELLO

VIOLA

VIOL

LUTE

LYRA

GAMBA

GUITARS

DOUBLE-BASS

Many people are already familiar with the information that a dendrochronological test may offer. However, If you are not, or are sceptical, misinformed or simply wish to know more about the subject, here are a few facts about this Science, its relevance and application to musical instruments, and in particular those from the violin family.

Which instruments lend themselves to dendrochronological testing?

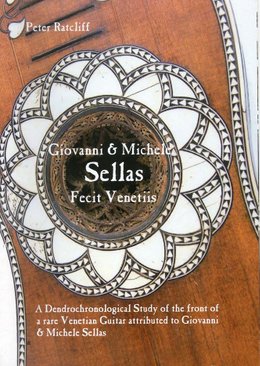

Instruments of the violin family, keyboards, as well as plucked instruments such as guitars and lutes, are almost invariably built with soundboards made from pieces of wood cut or split along the radial plane. The timber used on these soundboards is often spruce, more rarely another type of conifer such as pine or fir. These are all species that lend themselves to dendrochronological cross-dating.

Do all trees work?

For a given tree, the relative speed and physical characteristics of tree-growth during a given year (early spring growth, followed by “late” growth, forming the darker part of the tree ring) is replicated to a greater or lesser extent in trees that grew nearby. The extent of the similarities will depend on many factors. Some growing location are much more favourable than others to the widespread replication of the tree ring pattern. In general, high altitude produces a far more reliable dendrochronological signal than the one recorded by trees at the bottom of a valley.

Where do you start?

Many thousands of trees have been sampled and tested, from hundreds of locations. A great number have been logged, digitally stored and made available publicly by the International Tree-Ring Data Bank (I.T.R.D.B) for the benefit of the dendrochronological community. Some of these trees, growing several hundreds of kilometres apart, reveal very strong correlation between the pattern followed by their respective tree-rings. The main characteristic these trees have in common is a shared high altitude for their growth.

Musical instrument makers, throughout the centuries, have sought and favoured a tight, narrow growth for the spruce they would use on soundboards, or “bellies”. This type of morphology is often the result of growth at high altitude, combined with low temperatures. When measured accurately, the small, but perceptible differences in the consecutive width of the rings, is an accurate record of these year on year climate and environmental variations.

The aim of cross-dating in dendrochronology, is to identify separate ring patterns which track similar variations over a number of years.

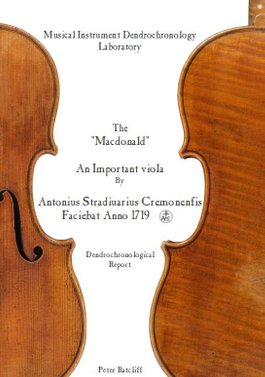

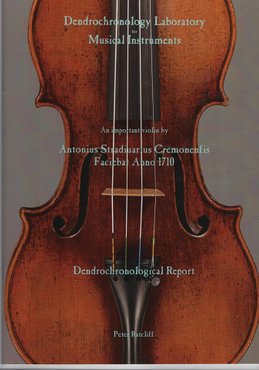

Following thousands of tests on instruments from every period throughout Europe, a large proportion of their soundboards have been conclusively dated. They then become an integral part of the reference data.

What else can you find out?

Whilst the dating is the primary aim of a dendrochronological analysis, and determining the period in which the tree was growing, other aspects, far more interesting and revealing than a date, can be investigated.

What is increasingly clear, is that, in certain parts of Europe during particular time periods, the spruce being harvested in selected or designated locations, on the whole ended up in specific instrument-making centres, or specific countries. These findings are based solely on the results of thousands of cross-dating tests, and not on a pre-conceived idea of the supposed origin of an instrument. The tests have identified several groups or clusters of instruments. These are often quite exclusive, which implies that the ring patterns common to instruments fitting within a particular cluster is not replicated in others, and that their data do not correlate. What this means for instruments, is that following a conclusive test obtaining highly significant results, both in terms of statistical correlation and visual similarities of the plotted data, the information revealed often exposes strong clues as to possible origin, or at the very least, offers an objective outlook on which to proceed.

Do you need the instrument in you laboratory?

Tests are carried out from very accurate tree-ring measurements. High-resolution digital images are becoming the preferred means from which to collect these ring-widths. The Web has been a great tool to speed up the whole process, allowing images to be sent from anywhere forgoing the need to examine the actual instrument.

How fast can I expect a result?

At times, speed of testing is paramount, often to help sway a decision on whether to acquiring an instrument or not. It is not unusual for a prospective purchaser to require a test on an instrument being offered at auction.

Why did my violin "not work"?

Whilst the soundboards of a great many instruments reveal a date, some do not. Although dendrochronologists possess large amounts of reference data from many parts of the Alps, and other mountain chains in Europe, there are still many dendrochronologically unexplored locations. Sometimes, the causes may be partial or complete deforestation, other times the lack of readily available old timber known to have grown locally. Reclaimed spruce, from high altitude locations is occasionally available for testing and in some instances has revealed exciting and unexpected results. Even when a conclusive date cannot be attributed to the wood, on occasions, a relationship with another or several other instruments can sometimes be established. Data from a newly tested violin, thought to be by Michelangelo Bergonzi, albeit remaining undated, was found to correlate with tree-ring data belonging to another two instruments. The levels of correlations were such, that the results fulfilled criteria for a same tree match. What were the other two instruments? Two violins by Michelangelo Bergonzi…

You can identifiy violins made from the same tree?

Maybe one shouldn’t be surprised at these findings, and same tree matches are identified on an increasing number of instruments. Indeed, many of the soundboards which are found to have originated within the same log, often turn out to be by the same maker or from the same workshop. The highest number of instruments so far identified fitting the same pattern includes 16 violins and violas made by Antonio Stradivari in the ten year period between about 1695 and 1705. Several other trees used, such as the one, which produced the 1716 Messiah belly together with soundboards of another two Stradivari from the following year, but also a P.G. Rogeri of 1721 have been identified. More surprisingly, a same tree match has been found on 5 instruments, 4 of which were made in Italy in towns as far apart as Venice and Naples via Cremona, the fifth in Spain, a good 30 years later